Nic Hess

Ferdinand

April 2 – June 4, 2022

In seinem Werk verwebt Nic Hess in zugleich handwerklich präziser und intellektuell scharfsinniger Manier Motive, die aus der Demontage von Materialien unterschiedlicher Herkunft stammen zu neuen Bildeinheiten. Ein aufwändiger Prozess der Zerlegung löst (Marken-)Symbole, Logos und Piktogramme einer universellen Konsumkultur, aber auch Ikonen aus Politik und Kulturgeschichte aus ihren ursprünglichen Kontexten. Aus diesem umfassenden Bildfundus schöpft Hess kontinuierlich, um neue Bedeutungszusammenhänge und pointierte Bildaussagen zu generieren, die sich mitunter objekthaft in die Dreidimensionalität ausdehnen und in klar austarierten Installationen direkt auf die unmittelbaren räumlichen Gegebenheiten beziehen.

Schon im Eingangsbereich begegnet man der undogmatischen Kombinatorik von Nic Hess, einer raffinierten Zusammeführung von Elementen aus konträren Bezugssystemen. Vor einer Wand, die mit verschlungenen Kurven aus Tape-Bändern beklebt ist, steht ein Podest mit einem liegenden Huhn, das ein Ei ausbrütet. Vor diesem Hintergrund, den Hess mit einem struppigen „Nest“ vergleicht, schlüpft statt des zu erwartenden Kükens ein Alligatorbaby. Dieser offensichtlichen, an die Gestalt eines Wechselbalg gemahnenden Unvereinbarkeit, wohnt eine unheilvolle, zumindest aber verunsichernde Ahnung einer aus den Fugen geratenen Ordnung inne: Sowohl als lakonischer Kommentar auf gesellschaftliche Fragen von Diversität, Distinktion und Diskriminierung gerichtet, als auch in Anspielung auf weltpolitisch aktuell bestehende Konfliktsituationen, in denen die Grenzen zwischen dem Eigenen und dem Anderen scharf und sogar mit kriegerischen Mitteln gezogen werden. Die filigrane Form an der gegenüber liegenden Wand hat Hess aus Operationsbesteck zusammengefügt. Es handelt sich einerseits um Einwegware aus China, die nach einmaligem Gebrauch entsorgt wird. Andererseits verwendet bzw. verwertet Hess genau die chirurgischen Utensilien, die der Arzt bei einem Eingriff an ihm selbst gebraucht und ihm anschließend überlassen hat. Sternförmig arrangiert ergeben die unterschiedlichen Größen und Öffnungsgrade der Scheren eine übergeordnete ornamentale Kreuzform, die sich als makabres Selbstportrait herausstellt.

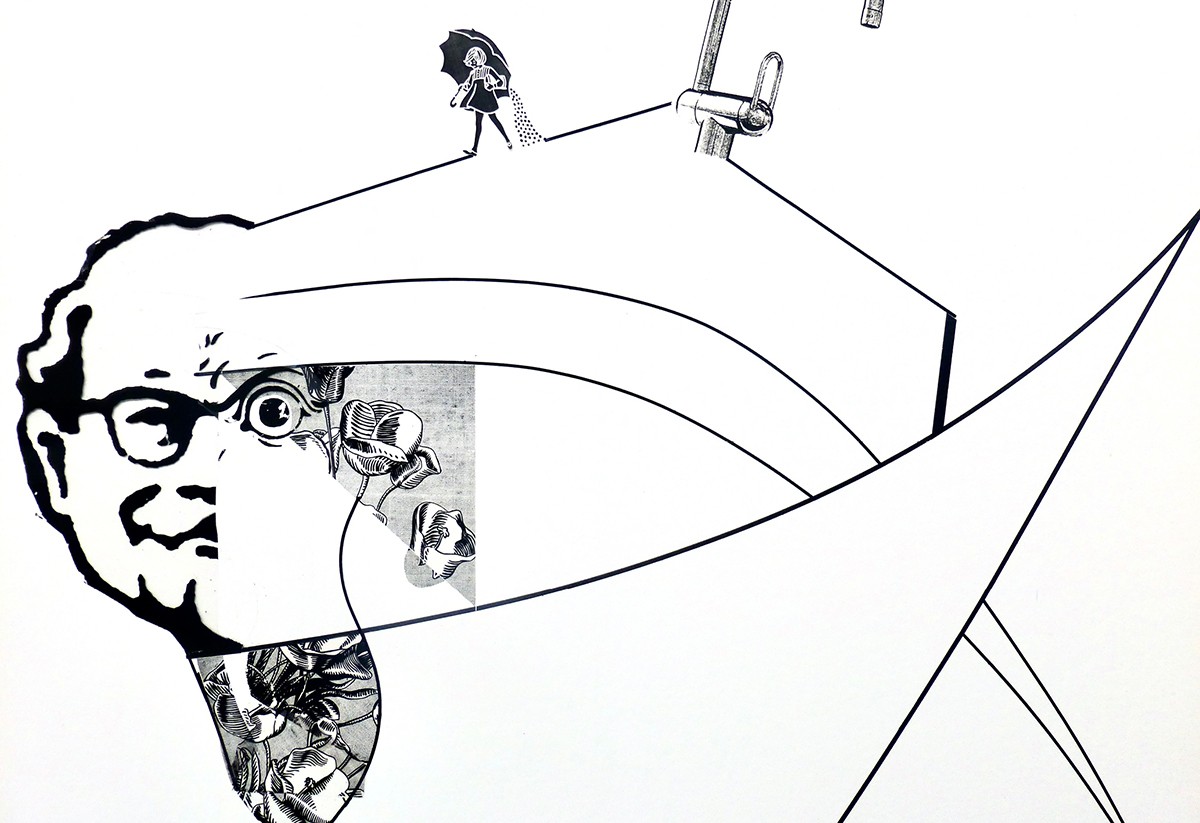

In den akribischen Papierarbeiten von Nic Hess treffen die Farbfelder von Richard Paul Lohse und das Twitter Logo zusammen, das Konterfeit von Berlusconi und eine Mondgesicht-Illustration verschmelzen, die Pokèmon Zeichnung des Sohnes setzt sich in einem streng konstruktivistischen Liniengerüst von Piet Mondrian fort. An anderer Stelle tritt das Spielfeld von Mensch Ärgere Dich Nicht, vervielfältigt und verschachtelt, in Erscheinung. Die Stuhlklassiker von Vitra werden in einem üppigen Blumenstrauß gereicht, von dem schon einige welke Blüten gefallen sind.

Seit einigen Jahren nutzt Hess die reichhaltigen Bibliotheksbestände seines verstorbenen Vaters, die eine große Anzahl an Bildbänden und Katalogen, aber auch Plakaten aus den Bereichen Bildender Kunst, Architektur und Design, enthielt. Daraus ergab sich die intensive Auseinandersetzung mit Ferdinand Hodler. Ihm ist auch der Ausstellungstitel Ferdinand gewidmet, der zugleich Würdigung und persönliche, vertrauliche Ansprache ist. Denn Hess ist seinem Landsmann näher gekommen, hat das Leben und Werk dieses bedeutendsten Schweizer Malers der frühen Moderne in zahlreichen Büchern buchstäblich auseinandergenommen und systematisch seziert. Dabei ist auch Biografisches in den bildhaften Vordergrund gerückt. So setzt sich die Collage Ferdinand aus

Fragmenten von Gemälden Hodlers zusammen. In der Mitte befindet sich ein Selbstportrait Hodlers, von Hess dynamisch schwungvoll ausgeschnitten um die kreiselnde Bewegung der gesamten Komposition aufzunehmen. Ausgehend vom Kopfbildnis fächert sich eine Reihe von blauvioletten Bergketten zum Gewand auf. Die zackige Silhouette der Gebirgsformationen setzt sich geradezu „natürlich“ fort in den hervorstehenden Wangenknochen und eingefallenen Gesichtszügen der Geliebten Hodlers, die er auf dem Sterbebett portraitiert hat. Ihr markantes Profil lockert Hess auf durch eine Gruppe von Delfinen. Fast scheint es, als würde Hess mit diesem fast dekorativ anmutenden Eingriff die Auflösung des schmerzhaften Motivs und somit emotionale Erlösung herbeiführen.

Hess‘ reflektierter Umgang mit Bildmaterial schlägt sich nicht nur formal, sondern auch inhaltlich nieder. Durch äußerst geschmeidige Übergänge bzw. nahtlose Verbindungen der Konturen und Linien stellt er den Eindruck einer formalen Geschlossenheit her, der über die extreme Uneinheitlichkeit und bisweilen brutale Widersprüchlichkeit der Motive und Sujets hinwegzutäuschen vermag und auch die Vorherrschaft bestimmter, sofort wiedererkennbarer Bilder nivelliert. Im Rhythmus zwischen Verdichtung und Auflösung bindet der elegante, linienbetonte Fluss seiner Kompositionen alle Fragmente behutsam ein und setzt sie in Beziehung zueinander, um neue Gewichtungen vorzunehmen. Dies betrifft auch die Ausstellung selbst. Im Untergeschoß stellt eine stellenweise herzrhythmisch ausschlagende Linie überraschende Verbindungen zwischen den heterogenen Elementen der Installation her.

Neben dem akribischen Aneinanderfügen von Ausschnitten zu einem bildnerisch kongruenten Zusammenhang, ist das Werk von Hess bestimmt durch die eingehende Beschäftigung mit den Bildsprachen der jeweiligen Künstler, auf deren Reproduktionen er zurückgreift. Vor dem Hintergrund seiner Aneignung der charakteristischen Stilmerkmale, konstruiert er die „Brooklyn Bridge“ in der Art von Piet Mondrian aus der Strukturierung des Bildraumes mittels rechtwinkliger – sich hier und da spielerisch verbiegender – Liniengefüge und dem farblichen Dreiklang Rot-Blau-Gelb. Portraits von Hodler führt Hess mehrfach im surrealistischen Sinne von René Magritte aus. Die plakative Pop Art-Sprache von Roy Lichtenstein komprimiert er zu einem Motiv, welches als Wappentier an propagandistische Formeln erinnert, jedoch durch die Brüchigkeit seiner Bestandteile und die damit einhergehende Unbeholfenheit als Karikatur derselben erscheint. Hintersinnig überlagert Hess die fremdenfeindliche Darstellung eines politischen Plakats, die im sprichwörtlichen schwarzen Schaf verbildlicht wird mit der Aufnahme einer Geisha, die gerade dadurch hervorsticht, dass ihre Haut – obgleich künstlich getüncht– besonders weiß ist. Hess illustriert eindrücklich das sprichwörtliche Schwarz-Weiß und die damit einhergehenden undifferenzierten Sichtweisen und Klischees, die sich als konstruierte – und gleichsam fiktive – Vorstellungen und Vorurteile erweisen.

Eine ausgeprägt bild- und informationskritische Haltung nimmt Hess ein in einem Werk, welches prominent an der Stirnwand der Galerie angebracht ist. Auch hier verwendet er ausschließlich Ausschnitte aus Landschaftsgemälden von Ferdinand Hodler, die er einer gelben und einer blauen Fläche zuordnet. Ihre zusammengesetzte Form entspricht den territorialen Umrissen der Ukraine, die sich hinter einem stilisierten Vorhang aus parallelen schwarzen Balken abzeichnet. Wie ein vorgeblendeter medialer Filter, trägt dieser zur möglichen Verfälschung des Bildes bei. Zu beiden Seiten des umkämpften Landes, tarieren Vater und Sohn auf einer Wippe das Kräfteverhältnis in ihrer Konstellation neu aus: Wer sitzt am längeren Hebel?

In his work, Nic Hess interweaves motifs derived from the dismantling of materials of various origins into new pictorial units in a manner that is both precise in terms of craftsmanship and intellectually sharp-sensed. An elaborate process of disassembly releases (brand) symbols, logos and pictograms of a universal consumer culture, but also icons from politics and cultural history from their original contexts. Hess continuously draws from this comprehensive pool of images to generate new contexts of meaning and pointed pictorial statements, which sometimes extend object-like into three-dimensionality and relate directly to the immediate spatial conditions in clearly balanced installations.

In the entrance area, one already encounters Nic Hess’s undogmatic combinatorics, a refined combination of elements from contrary reference systems. In front of a wall covered with intricate curves made of tape stands a pedestal with a lying chicken hatching an egg. Against this background, which Hess compares to a shaggy “nest,” a baby alligator hatches instead of the expected chick. This obvious incongruity, reminiscent of the figure of a changeling, has an ominous, or at least unsettling, sense of an order out of joint: both as a laconic commentary on social issues of diversity, distinction, and discrimination, and as an allusion to current conflict situations in world politics, in which the boundaries between one’s own and the other are drawn sharply and even by warlike means. The filigree form on the opposite wall was assembled by Hess from surgical instruments. On the one hand, they are disposable goods from China that are disposed of after a single use. On the other hand, Hess uses or recycles exactly the surgical utensils that the doctor used during an operation on himself and then gave to him. Arranged in a star shape, the different sizes and degrees of opening of the scissors result in a superordinate ornamental cross shape that emerges as a macabre self-portrait.

In the meticulous paper works of Nic Hess, the color fields of Richard Paul Lohse and the Twitter logo come together, the likeness of Berlusconi and a moon face illustration merge, the Pokèmon drawing of his son continues in a strictly constructivist framework of lines by Piet Mondrian. Elsewhere, the playing field of Men, Don’t Get Angry appears, multiplied and interlaced. The chair classics by Vitra are presented in a lush bouquet of flowers, from which a few wilted blossoms have already fallen.

For some years now, Hess has been making use of the rich library holdings of his late father, which contained a large number of illustrated books and catalogs, as well as posters from the fields of fine art, architecture and design. This led to an intensive study of Ferdinand Hodler. The exhibition title Ferdinand is also dedicated to him, which is both a tribute and a personal, confidential address. For Hess has come closer to his compatriot, has literally taken apart and systematically dissected the life and work of this most important Swiss painter of early modernism in numerous books. In the process, biographical aspects have also moved into the pictorial foreground. The collage Ferdinand, for example, is composed of fragments of Hodler’s paintings. In the center is a self-portrait of Hodler, dynamically cut out by Hess in order to take up the circular movement of the entire composition. Starting from the head portrait, a series of blue-violet mountain ranges fan out to the robe. The jagged silhouette of the mountain formations continues almost “naturally” in the prominent cheekbones and sunken features of Hodler’s mistress, whom he portrayed on her deathbed. Hess softens her striking profile with a group of dolphins. It almost seems as if Hess is bringing about the resolution of the painful motif and thus emotional redemption with this almost decorative intervention.

Hess’ reflective handling of pictorial material is reflected not only formally, but also in terms of content. Through extremely smooth transitions or seamless connections of contours and lines, he creates the impression of formal unity, which is able to disguise the extreme inconsistency and sometimes brutal contradictoriness of the motifs and subjects, and also levels out the predominance of certain, immediately recognizable images. In the rhythm between condensation and dissolution, the elegant, linear flow of his compositions carefully integrates all fragments and sets them in relation to each other in order to carry out new weightings. This also applies to the exhibition itself. In the basement, a line that in places strikes out in a heartbeat creates surprising connections between the heterogeneous elements of the installation.

In addition to the painstaking assembly of excerpts into a pictorially congruent context, Hess’s work is determined by an in-depth study of the pictorial languages of the respective artists, whose reproductions he draws upon. Against the background of his appropriation of the characteristic stylistic features, he constructs the “Brooklyn Bridge” in the manner of Piet Mondrian from the structuring of the pictorial space by means of right-angled – here and there playfully bending – line structures and the color triad red-blue-yellow. Portraits by Hodler are repeatedly executed by Hess in the surrealist spirit of René Magritte. He compresses the striking Pop Art language of Roy Lichtenstein into a motif which, as a heraldic animal, is reminiscent of propagandistic formulas, but which appears to be a caricature of them due to the fragility of its components and the resulting awkwardness. Hess subtly superimposes the xenophobic depiction of a political poster, which is illustrated in the proverbial black sheep, with the image of a geisha, who stands out precisely because her skin – although artificially whitewashed – is particularly white. Hess impressively illustrates the proverbial black and white and the accompanying undifferentiated views and clichés, which prove to be constructed – and, as it were, fictitious – ideas and prejudices.

Hess takes a distinctly image- and information-critical stance in a work prominently displayed on the front wall of the gallery. Here, too, he exclusively uses excerpts from landscape paintings by Ferdinand Hodler, which he assigns to a yellow and a blue surface. Their composite form corresponds to the territorial outlines of Ukraine, which is outlined behind a stylized curtain of parallel black bars. Like a pre-screened media filter, it contributes to the possible falsification of the image. On both sides of the embattled country, father and son rebalance the balance of power in their constellation on a seesaw: Who is sitting on the long end of the stick?