Martin Gerwers

Neue Werke

September 4 – November 6, 2021

Martin Gerwers Werke, wir zeigen drei neue skulpturale Arbeiten sowie Gemälde, bewegen sich in einem Spannungsfeld zwischen Malerei und Skulptur. Er untersucht mit ihnen das Verhältnis von Farbe und Raum. Für den / die Betrachter*in werden die raumgreifenden Malereien und Skulpturen, die sich durch ihre Vielansichtigkeit auszeichnen, erst dann vollständig erfahrbar, wenn sie / er aktiv um die mehrfarbigen Objekte schreitet. So ergibt sich – je nach Standpunkt – eine Vielzahl von Seheindrücken.

Und natürlich ist auch sonst die Wahrnehmung des Originals von größter Bedeutung. Das wird an der ersten Skulptur der Ausstellung besonders deutlich. Sie wirkt anfangs so, als wären die opaken, schwarzen Flächen, die wir zunächst sehen, samtige, geschlossene Oberflächen. Tatsächlich aber handelt es sich um schwarze Löcher, die nur undurchdringlich anmuten. Diese Seite des Objekts ist einfach eine offene Seite eines Volumens, das auf dreieckigem Grundriss basiert und hinten spitz zuläuft. Es scheint in seinem Innenraum schwarz zu sein. Schwarz? Nein, nicht ganz, es handelt sich um Flächen, die sich bei genauem hinsehen als extrem dunkelrot oder -braun, beziehungsweise dunkelblau entpuppen.

Wir kennen dieses Phänomen, dass man sehr lange hinsehen muss, um überhaupt Farben zu sehen, aus dem Werk von Ad Reinhardt. Erst nach längerer Betrachtung fängt unser Sehorgan an, die neun einzelnen Quadrate seiner Gemälde differenzierten Farben zuzuordnen. Beim flüchtigen Blick auf die Reproduktion bleibt das Farb-Erlebnis aus. Genauso kommt es auch bei Martin Gerwers auf die in die Zeit gestreckte, konzentrierte Wahrnehmung durch das natürliche Auge an.

Alle drei Skulpturen der Ausstellung sind hinsichtlich ihrer Standfestigkeit höchst sensibel. Und hier liegt ein bemerkenswerter Unterschied zu vielen dreidimensionalen Kunstwerken aus den USA der 1960er und 1970er Jahre. Denn selbst wenn Plastiken von Richard Serra höchst labil wirken, sind sie doch tatsächlich eher stabil – und damit ganz anders als die Arbeiten von Martin Gerwers, deren einzelne Elemente in labiler Lage aufeinander balancieren und uns den Eindruck geben sie müßten jeden Moment herabfallen.

Aber nicht nur an Werke von Serra können wir denken, wenn wir Gerwers‘ Objekte sehen, sondern auch – zum Beispiel – an manche Werke von Donald Judd, die deshalb nicht zusammenfallen, weil jedes Element der Statik dient: die Drahtseile schaffen Spannung zwischen den Seitenteilen und denen, die sich vor Kopf befinden. So entsteht ein ausbalanciertes Ganzes, das gleichwohl leicht und labil wirkt. Während jedoch das Objekt von Judd transparent nicht nur hinsichtlich einiger Elemente des verwendeten Materials ist, sondern im Grunde auch insgesamt hinsichtlich der Möglichkeit, die Statik zu verstehen, verunklart Gerwers diese Möglichkeit. Es ist eben gerade nicht ohne weiteres einsehbar, dass seine Objekte so wie sie stehen auch tatsächlich stehenbleiben.

Andere US-amerikanische Skulpturen aus den 1960er und 1970er Jahren, die mit dem Attribut „minimal“ beschrieben werden und die sich schon allein deshalb mit Gerwers in Beziehung setzen lassen, sind etwa solche von Robert Morris. Aber auch hier gilt, dass Morris‘ Strukturen von vorneherein durchschaubar und lesbar sind, Gerwers Werke dagegen opak und geheimnisvoll bleiben.

Die Vergleiche zwischen Gerwers und den früheren Beispielen dreidimensionaler Kunst sind deshalb sinnträchtig, weil sich mit ihnen besondere Eigenschaften im Werke Gerwers‘ verstehen lassen. Anders als seinen US-amerikanischen Kollegen geht es ihm eben nicht um die Vermeidung von allem, was in den USA als „europäisch“ gebrandmarkt wurde: Narration, Mystik, Relationalität, um nur ein paar Schlagworte zu nennen. Es geht ihm vielmehr darum, gerade dies zu schaffen: ein Erlebnis voller Mystik, und Überraschung.

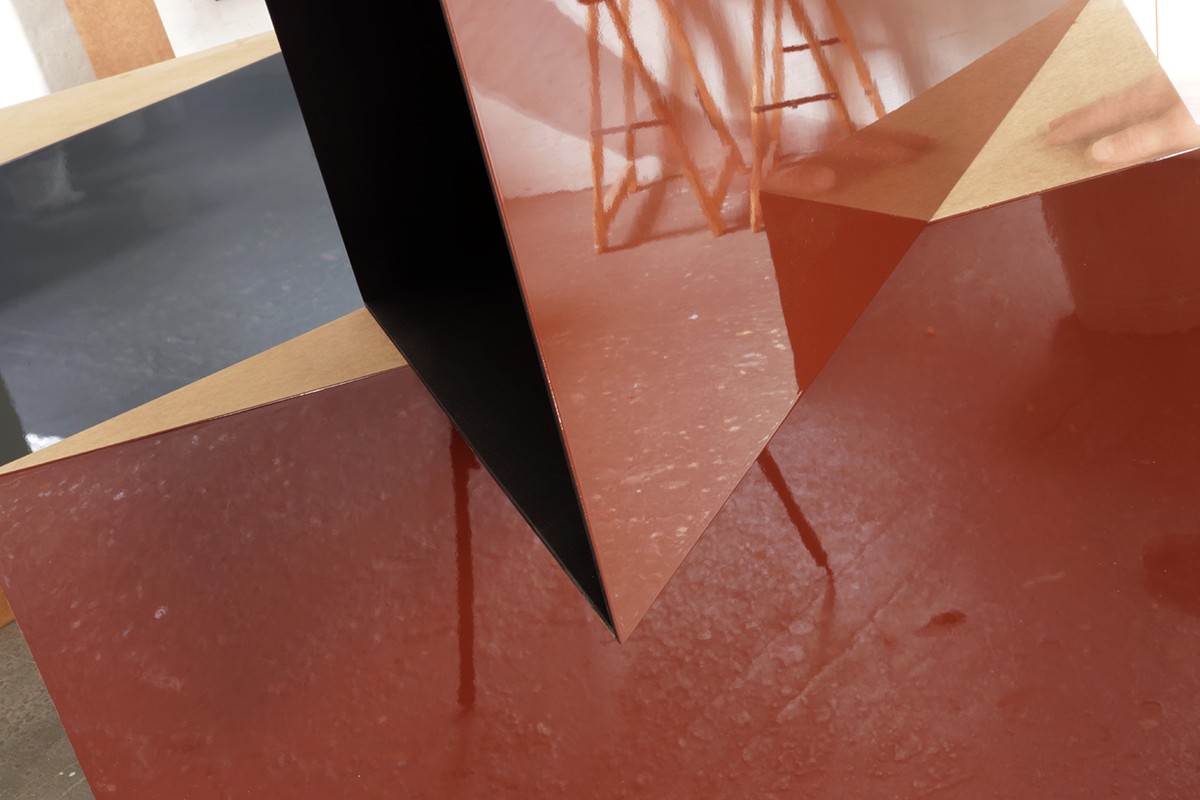

Dies gilt auch für den Umgang mit der Farbe: sie ist bei Gerwers den Materialien nicht inhärent, sondern appliziert. Und dieser Prozess geschieht mit teils noch sichtbarem Pinselstrich, jedenfalls mit einer noch wahrnehmbaren Spur von „gemacht-sein“ (im Unterschied zu „produziert werden“). Und vielleicht ist der wichtigste Unterschied zu den Amerikanern, dass für Gerwers die Komposition, das – im engen, lateinischen Sinne des Wortes – zusammenstellen der Farben, von höchster Bedeutung ist – subjektiv und stark abhängig von seinem eigenen farblichen Empfinden. Zugleich spielt er mit den Möglichkeiten der Materialien und ihrer ästhetischen Wirkung, weil er einige der Oberflächen spiegelglatt und perfekt schafft (bzw. in einer Lackiererei für Autos hat herstellen lassen).

Das heißt, dass es für Gerwers nicht ein entweder / oder gibt, sondern ein sowohl als auch: wir sehen sowohl klare, minimalistische Formen im Raum, die – auf den ersten Blick – durchschaubar sind und in die wir zum Teil auch hineinschauen und die Binnenstruktur erfassen können. Und zugleich verstehen wir die labil zusammengestellten Formen nicht ohne weiteres. Vielmehr ist es sogar so, dass es kaum möglich ist, sich im umgehen der Skulpturen einzuprägen / zu merken, was vorher da war und wie es zusammengestellt war und wie es aussah.

Ein Wort noch zu den scharfen Kanten der Objekte und dazu, wie die Farben an ihnen wahrgenommen werden: je Element auf dreieckigem Grundriss können wir immer nur zwei Farben sehen. Das ist ein fast als digital zu beschreibender Prozess: wir sehen etwas blau und schwarz oder blau und grau oder grau und schwarz. Aber wir sehen eben nicht die jeweilige Rückseite des gerade in den Fokus genommenen Volumens. Durchschaubarkeit à la Judd oder Frank Stella („what you see is what you get“) ist nicht gegeben. „Digital“ ist dieser Prozess, weil es hinsichtlich der Farbzusammenstellungen nur ein so oder so gibt, keine Mischfarben und auch nicht die Wahrnehmung von drei Farben auf einem skulpturalen Element zugleich.

Dass Martin Gerwers ursprünglich aus der Malerei kommt und sich mit Malerei einen Namen geschaffen hat (er war zum Beispiel 1996 Preisträger des renommierten Ars Viva-Kunstpreises des Bundesverbands der Deutschen Industrie) wird deutlich, wenn man sich die Gemälde aus der Ausstellung vor Augen führt. Diese Bilder, die auf Holz gemalt sind und in den Raum treten, können als zweidimensionale Abwicklungen je einer Skulptur gelesen werden. Alle drei horizontal nebeneinander befindlichen Flächen kann man als jeweilige Seiten eines Objektes auf dreieckigem Grundriss verstehen, so dass man sich vorstellen kann, die flachen Tafeln wieder zu Objekten zu machen und dann jeweils drei Elemente aufeinander zu stellen.

Abschließend sollen hier noch einmal zwei Aspekte stark gemacht werden: zum einen ist es das gemacht-sein dieser Werke, die quasi-perfekt sind, aber eben nicht eine 100%ige, industriellen Prozessen vorbehaltene, Perfektion aufweisen. Damit schaffen sie für uns als Rezipient*innen die Möglichkeit, eine Beziehung herzustellen auf einer menschlichen Ebene. Zum anderen soll der Begriff der Poesie ins Spiel gebracht werden. Von den Werken Martin Gerwers‘ geht eine sich unserer Sprache und unseren kognitiven Urteilen entziehende oder über sie hinausgehende Wirkung aus. Das ist etwas, was von Minimal Artists unbedingt vermieden werden wollte. Aber hier, bei Gerwers, entsteht Leben, wahrnehmbares Erlebnis und damit eine Form von Glück.

Philipp von Rosen, September 2021

Martin Gerwers‘ works, we show three new three-dimensional works as well as paintings, are situated in a field of tension between painting and sculpture. With them he investigates the relationship between color and space. For the viewer, the expansive paintings and sculptures, which are characterized by their multi-visuality, can only be fully experienced when he / she actively walks around the multi-colored objects. This results in a multitude of visual impressions – depending on the viewpoint.

And, of course, the perception of the original is of utmost importance in other respects as well. This is particularly evident in the sculpture Untitled (July). It appears as if the opaque, black surfaces we initially see were velvety, closed surfaces. In fact, however, they are black holes that only appear impervious. This side of the object is simply an open side of a volume based on a triangular ground plan and pointed at the back. And it seems to be black in its interior. Black? No, not quite, we are talking about surfaces that, on closer inspection, turn out to be extremely dark red or brown, or dark blue.

We know this phenomenon, that you have to look very long to see colors at all, from the work of Ad Reinhardt. Only after prolonged observation do our eyes begin to assign the nine individual squares of his paintings to differentiated colors. A glimpse at the reproduction does not give us the experience of color. In the same way, Martin Gerwers‘ work depends on the concentrated perception by the natural eye, stretched out in time.

All three sculptures in the exhibition are highly sensitive in terms of their stability. And here lies a remarkable difference to many three-dimensional works of art from the USA of the 1960s and 1970s. For even if sculptures by Richard Serra seem highly unstable, they are in fact rather stable – and thus quite different from the works of Martin Gerwers, whose individual elements balance on top of each other in an unstable position and give us the impression that they might fall at any moment.

But it is not only works by Serra that we can think of when we see Gerwers‘ objects, but also – for example – some works by Donald Judd, which do not collapse because each element serves the static: the wire ropes create tension between the side parts and those in front. This results in a balanced whole that nonetheless appears light and unstable. However, while Judd‘s object is transparent not only with regard to some elements of the material used, but basically also overall with regard to the possibility of understanding the statics, Gerwers obscures this understanding. It is precisely not readily apparent that his objects actually remain standing as they are.

Other American sculptures from the 1960s and 1970s that are described with the attribute „minimal“ and that can be related to Gerwers for this reason alone are, for example, those by Robert Morris. But here, too, Morris‘s structures are transparent and readable from the beginning, while Gerwer‘s works remain opaque and mysterious.

The comparisons between Gerwers and the earlier examples of three-dimensional art are meaningful because they can be used to understand particular qualities in Gerwers‘ work. Unlike his U.S. colleagues, he is not concerned with avoiding everything that has been branded „European“ in the United States: narration, mysticism, relationality, to name just a few keywords. Rather, he is concerned with creating just that: an experience full of mysticism, and surprise.

This also applies to his handling of color: in Gerwers‘ work, it is not inherent in the materials, but applied. And this process takes place with brushstrokes that are sometimes still visible, or at any rate with a still perceptible trace of „being made“ (as opposed to „being produced“). And perhaps the most important difference to the Americans is that for Gerwers the composition, the – in the close, Latin sense of the word – putting together of the colors, is of the highest importance – subjective and strongly dependent on his own sense of color. At the same time, he plays with the possibilities of materials and their aesthetic effect, because he creates some of the surfaces mirror-smooth and perfect (or has had them made in a paint shop for cars). This means that for Gerwers there is not an either / or, but a this and that and thus we see both: clear, minimalist forms in space, which – at first glance – are transparent and into which we can partly look and grasp the internal structure. And at the same time, we do not readily understand the unstably assembled forms. Rather, it is even so that it is hardly possible to memorize / remember in the circumvention of the sculptures what was there before and how it was put together and what it looked like.

Let me say a word about the sharp edges of the objects and how the colors on them are perceived: for each element on a triangular ground plan we can always see only two colors. This is a process that can almost be described as digital: we see something blue and black or blue and gray or gray and black. But we do not see the respective reverse side of the volume that has just been brought into focus. Transparency à la Judd or Frank Stella („what you see is what you get“) is not given. This process is „digital“ because, with regard to the color combinations, there is only a one way or the other, no mixed colors, and also not the perception of three colors on one sculptural element at the same time.

That Martin Gerwers originally comes from painting and has made a name for himself with painting (he was, for example, the winner of the prestigious Ars Viva art prize of the Federation of German Industries [BDI] in 1996) becomes clear when one considers the paintings from the exhibition. These paintings, which are painted on wood and emerge into the room, can be read as two-dimensional unwindings of one sculpture each. All three horizontally juxtaposed surfaces can be understood as respective sides of an object on a triangular ground plan, so that one can imagine turning the flat panels into objects again and then placing three elements on top of each other.

Finally, two aspects should be emphasized here: on the one hand, it is the being-made by the artist of these works, which are quasi-perfect, but do not exhibit a 100% perfection reserved for industrial processes. Thus they create for us as recipients the possibility of establishing a relationship on a human level. On the other hand, the concept of poetry should be brought into play. Martin Gerwers‘ works have an effect that eludes or transcends our language and cognitive judgments. This is something that Minimal Artists have tried to avoid at all costs. But here, with Gerwers, life, perceptible experience, and thus a form of happiness emerges.

Philipp von Rosen, September 2021